Molly Bloom’s Implausible Origins

Part 1: Her Moorish Mother, Lunita Laredo

Left image

Right image

Text

Molly Bloom’s Implausible Origins. Part 1

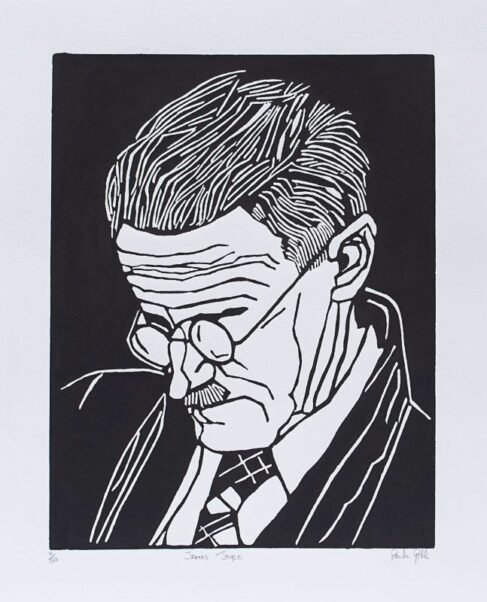

In Ulysses, James Joyce believed he had created a picture of the metropolis of Dublin so compelling in its detail and truthfulness to life that were the city to be demolished it could be recreated from the pages of his book. He spurned fictional deviation from the realistic, even while immersing the real in a sea of symbolism. In his book Conversations with James Joyce, Arthur Power notes that for Joyce realism was all-important. ‘In realism,’ he quotes Joyce as saying, ‘you are down to fact on which the world is based: that sudden reality that smashes romanticism into a pulp (…). In Ulysses I tried to keep close to fact’. As he admitted in reference and contrast to W.B. Yeats, in a sense he lacked imagination and he largely spun his epic out of the cloth of his personal life. For the most part he peopled his fictional city with characters little altered and drawn from his encounters with or recollection of the citizens of Dublin. There are well more than a hundred historical persons to be found interred in Glasnevin Cemetery that feature as minor and only occasionally re-named characters in his novel. The characteristics he depicted, however, were in the main true-to-life. Simon Dedalus is, for example, an accurate (if benign) portrait of his father, as is the ghost of his dead mother that haunts him (as Stephen) and who surfaces accusingly in the ‘Circe’ episode. Others are pieced together from multiple counterparts. For Joyce, living and writing were intimately interwoven and symbiotic, and his personhood was forged not alone in the streets he traversed in Dublin, in Trieste, in Paris and elsewhere, but also in the writerly shaping over several texts of his alter-ego: Stephen. In a real sense, he wrote his full self into existence.

Where this lack of imagination (or aversion to the purely fictive) weakens the cohesion of the world he portrays in Ulysses is in those areas where Joyce strays beyond the familiar, relying as best he can on the written accounts of others of the subjects he is concerned with. Thus, for example, he scoured histories of Gibraltar for realistic details with which to shape the history of one of his most significant characters: Molly Bloom. He had to provide her inter alia with a background: with an origin, with parents, with childhood memories, with emigration to Dublin and with encountering, being wooed by and marrying Leopold Bloom. As I shall illustrate in this two-part essay, he failed in this writerly endeavour, and in embodying Molly he was rather more confounded than inspired by the literature he read. Even on the solid (to him) streets of Dublin, in so significant a matter as how, when and where she and Leopold Bloom first met, something he should easily as author have determined, he left us with impossible, conflicting accounts. But I wish here to focus not on the Dublin years, but on her days on the Rock: in particular on Molly’s mother. In a subsequent essay I address the matter of her father as Joyce, struggling with a need for realism, wrote her progenitors somewhat chaotically into existence.

We first come upon the person of Molly’s mother rather late in the day, so to speak: in the post-midnight eighteenth and final chapter ‘Penelope’. Indeed, one of the very last additions made to the text of the novel was Molly’s admission of never having had a caring mother—something ‘what I never had’. It is here in ‘Penelope’ that we first encounter Molly’s voice: absent elsewhere in the book with the sole exception of the short mumbled utterance in the first of the ‘Bloom’ chapters, ‘Calypso’, set in the early morning as Bloom sets about preparing his and her breakfast. (Molly’s subsequent appearance and discourse in ‘Circe’ are hallucinated.) We learn only in ‘Penelope’ that this little ritual is normal practice in the Bloom household where Molly comments on how she loves to hear him ‘falling up the stairs of a morning with the cups rattling on the tray’. Indeed one of the triumphs of Bloom’s personal odyssey on 16 June1904 is to alter this pattern and insist in a reassertion of his primacy on having a breakfast of eggs brought up to him on the following morning.

In ‘Calypso’, the only episode other than ‘Penelope’ that is physically inhabited by Molly, all we hear from her is a version of the word ‘no’: ‘Mn’. No, she did not want anything for breakfast. (Famously, her last word in ‘Penelope’ is ‘yes’.) Her mumble recalls for us the first utterance of the Bloom chapters: the cat’s ‘mkgnao’.

This short interaction, and his wife’s accompanying turning over in the bed upstairs, causing a jingling of the brass quoits of the bedstead, brings to Bloom’s mind Molly’s father (other than Molly and the cat the first person to whom he refers). Later in the day, Bloom’s thoughts intermittently return to the figure of the father’; however, at no point does he consider for a moment her mother, of whom he has clearly almost no knowledge and has never met. We have to wait until ‘Penelope’ to learn anything about her: she was Spanish, was physically attractive—possibly sensually so—and was ‘jewish looking’—but not necessarily Jewish—and that her ‘beautiful’ name was ‘Lunita Laredo.’

Twice in the course of the novel Bloom refers to his wife’s alluring, Moorish looks: looks she must have inherited from her mother. Her father the moustached, pipe-smoking Major Tweedy, hailing (seemingly) from Dublin, was decidedly not Moorish. This gives us by inference an outline of the absent mother: a good-looking, possibly Jewish woman with Moorish ancestry resident in Gibraltar. Gibraltar is a small place and its Jewish population was in the relevant years narrowly defined. We can accordingly uncover (outside the pages of Ulysses) much of the historical social context of life for this exotic (if fictional) woman.

Phillip Herring does precisely this in his well-researched paper, Towards a Historical Molly Bloom. He emphasises the poverty found in Gibraltar in the nineteenth century, the infectious mosquitoes swarming in the stagnant water, and the chasm that existed between colonist and native, British and Spanish, Jew and Christian, master and servant, and garrison and town. Joyce’s idealised account of Molly’s life on the Rock entirely veils the reality. In 1870, the year Molly was born, the island was heavily populated (10,116 persons) with little space and less privacy for each individual. Most of the inhabitants were church-mouse poor with few, if any, possessions. Smuggling, money-changing, and selling tapestries were the chief businesses of the locals; and these occupations led on to riches only in rare cases. The British maintained a strict policy of keeping the local Spanish out, and no servants (like Molly’s old cantankerous Mrs Rubio) were permitted to remain in the fortress overnight, irrespective of their business.

The Jews originally came to Gibraltar from Morocco to escape persecution. Once there, they were admittedly somewhat less persecuted than formerly: yet as a race they were merely tolerated and formal laws (if not strictly implemented) precluded their taking up legal residency. In response, they bunched themselves together into a tightly knit, semi-isolated community. The threads of their kinship were knotted into their dark language, customs, and history. Intercourse outside the group—other than what was required for commercial purposes and the needs of day-to-day living—was both tacitly proscribed and unwanted; and, not surprisingly, marriage outside the circle was utterly taboo. A Jewish maiden seeking to marry a Christian man, say, would have been shunned and cast out by her family.

On the other side of the coin was the equally tightly knit, well-manned British garrison in Gibraltar: the barracks where Major Tweedy, Molly’s father, would have lived while stationed there. Again, this community formed a closed group with only limited intercourse with the ‘scorpions’ (the natives) and the motley, if exotic, blend of oddly dressed, redoubtable specimens, dealers and down-and-outs, Spanish included, that thronged busily together in what remained a narrow and confined space. The soldiers, whenever the opportunity arose, did frequent the many pot-houses, grog and wine-shops, and the whorehouses of the adjacent smugglers’ Spanish paradise, La Linéa; but it was unthinkable for a British officer to form a serious relationship with a native girl; indeed, he would have been immediately transferred elsewhere by his superior officers (possibly to a lunatic asylum) had he proposed marriage to such a woman.

This leaves us close readers of Ulysses and sighing devotees of Joyce’s uncanny adhesion to the actual with a hugely implausible marriage of Molly’s progenitors—if marriage it was—given the historical facts that pertain to Gibraltar, and, in addition, an equally implausible girlhood for Molly.

We have two small clues as to Joyce’s hopes for making Molly’s mother less than fantastical (something he openly deplored in literature): the names Lunita and Laredo. The latter was indeed a real-life Jewish name borne by several persons living in Gibraltar at the time, just as families named Bloom were to be found in Dublin. Joyce would have come across the name Laredo while perusing the Gibraltar Dictionary and Guidebook for 1902. Lunita, a diminutive form of the name Luna, was common among Jewish women in Gibraltar, as was Gimol, the diminutive of which is Molly. Indeed, Philip Herring directs us to the novella Luna Benamor, written in 1909 by Vicente Blasco-Ibánez (1867-1928) and translated into English in 1919 (when Joyce was working on ‘Penelope’), that describes the precise crisis faced by a young and beautiful Jewish woman of that name, living in Gibraltar in its closed community, who falls in love with an outsider, Luis Aguirre. An aristocratic Spaniard, he is on his way to becoming a consul in Australia and wants her to join him in his new life. Love—wisely—does not stifle the tedious exigencies of practicality. The young woman remains behind with her own kind, the religious cage remains firmly in situ, and the dashing young man sails off to experience—one hopes—a less disruptive relationship. (The parallels with Joyce’s short story ‘Evelyn’ are striking.)

Joyce may have read this novel, and he may even have considered in its light Molly’s mother’s plight (let us call it that) when she putatively had to make a life-choice: to leave behind her historical and familial roots (even if estranged from them) and accompany the drum-major to Dublin or to quit the garrison, return to the town and to her Jewish relatives, and, once there, following a reconciliation seek to recover her natural place among her own people. As we know, Lunita Laredo never boarded the boat heading for Dublin and presumably remained in Gibraltar.

We are still left with the problems of how Laredo met Tweedy and what on earth happened to her after their short time togerther. Joyce left the picture unfinished: hardly an outline, if not entirely unpainted. We can only speculate. Molly, as a motherless ‘daughter of the regiment,’ could not have had a normal upbringing. Lunita Laredo could never (in those times) have become Lunita Tweedy. She could have been—possibly was—a prostitute from La Linéa who fell pregnant, had the child, left it with the father, and returned to the brothels. Or she could have been a daughter of a strict Sephardic Jewish family that, to their shame, fell for the Irish officer, became enceinte, and gave birth to a daughter.

At this point we are left with two possibilities: first, that Luna died in childbirth or, second, that having delivered herself of the child she fled Gibraltar with its stifling, love-excluding social conventions and restrictions (but leaving her lover and daughter behind). The happier end of a mixed marriage and subsequent reconciliation of the newlyweds with the bride’s mother, father, sisters, brothers, cousins, and grandparents was absolutely off the cards. If Luna died in giving birth, the surviving daughter (Molly) may justifiably have fears regarding birth, as indeed she has. But even this story is unlikely. Molly holds her mother responsible for naming her (‘[my] mother whoever she was might have given me a nicer name’); and fixing a gendered name to (that is, christening) a child generally postdates the child’s birth.

Molly makes an abstruse reference to the circumstances predating her marriage, aged eighteen, to Bloom (ultimately, on this long double-exile view, her failed redeemer) when she comments ‘he hadn’t an idea about my mother till we were engaged otherwise hed never have got me so cheap as he did.’ This can only be interpreted as meaning that had the circumstances of her birth been different—had her father been a Sephardic Jew, possibly a rich money-changer or a dealer in tapestries, and had her parents continued to live in the bosom of a closed community in Gibraltar, then Molly would have presented an entirely different marriage prospect than that she ended up doing: the illegitimate daughter of an irresponsible couple. Molly herself muses on yet another unrealised scenario. Wrongly recollecting that the Prince of Wales visited Gibraltar at the time of her birth (he never did), she thinks: ‘H R H he was in Gibraltar the year I was born I bet he found lilies there too where he planted the tree he planted more than that in his time he might have planted me too if hed come a bit sooner then I wouldnt be here as I am.’ Indeed not.

One final point of interest leaves us profoundly in the dark: what history did Tweedy relate to Molly about her mother? Molly has no recollections of her mother’s presence during her life in Gibraltar. She does not even recall what she looked like, though she is told by her father that she had inherited her mother’s eyes and figure. Also, when Molly speaks of the importance of a mother in the rearing and safe-keeping of a child, she speaks of this as something ‘what I never had.’ We can safely assume that Lunita was absent throughout her daughter’s girlhood: but absent where? In the grave or in Spain, presumably; but what account would the father have given his daughter when, quite naturally, she asked who and where her mother was. We know that Molly knew her mother’s name and her race, hence some version was passed on to her; but on this matter Joyce remains deafeningly silent.

While there is a grave in the Jewish Cemetery in Gibraltar in which are interred the mortal remains of a Lunita Laredo, nothing of this woman’s life – possibly even the existence of the grave – was known to Joyce. Hers was a name, a tabula rasa, come upon in a guidebook. Ultimately, he was unable convincingly or coherently to absorb her into his novel. In failing in this, he also failed in creating a realistic or even plausible girlhood history for his most famous female character. In depicting her father, Major Tweedy, the subject of the second part of this essay, he was, as we shall see, perhaps even less realistic. Joyce was deficient in imagination, in the novelist’s art of creating realistic characters out of thin air. Those that are cleanly delineated, such as the family members of the Dedalus household and their Dublin friends, are lifted almost unaltered out of his personal history (in part directly out of his diaries and notebooks) and pasted into his novel. He was indeed at bottom ‘a scissors and paste man’, but could ply his tools with exquisite sensitivity and intelligence.