The Correspondence

of Daniel O'Connell

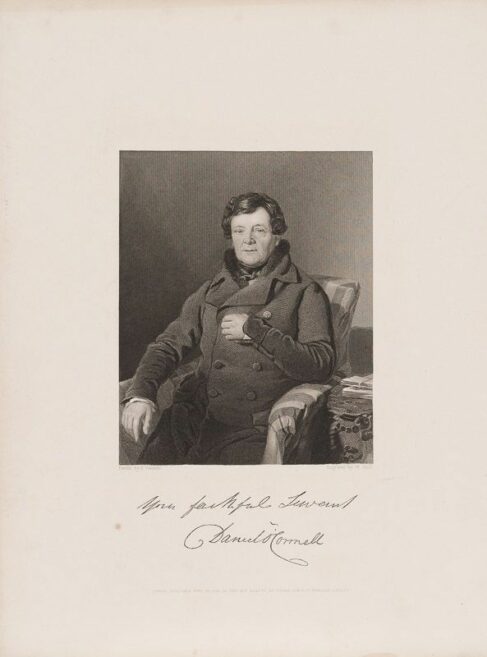

Left image

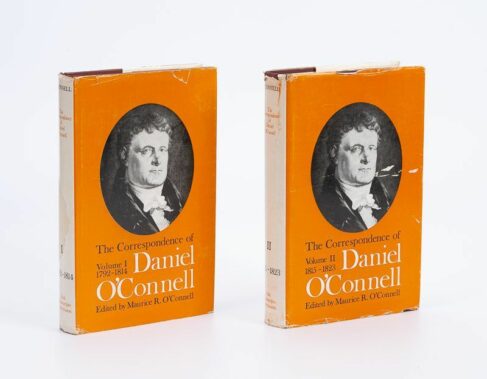

Right image

Text

The Correspondence of Daniel O’Connell

It lightens my heart to write to you. (London. March 11, 1833.)

The great Irish statesman Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847), hailing from Kerry, loved to write letters and these letters radiate the overflowing light of his heart. The Correspondence of Daniel O’Connell, in eight volumes, effectively narrates the whole of his adult life. The letters are written contemporaneously with the events recounted and can be read as a kind of continuous diary; and where the letters are paired with the correspondent’s answer, the reader can listen in to a vivid dialogue.

The Correspondence reveals the author’s personality in vivid detail and charts the evolution of O’Connell’s thoughts and feelings. Through the window of these pages, we see the motives and causes, grounded in lived experience, that spurred his powerful political work. The ‘Liberator’, as he is known, is presented here as a man of action, with an immediacy and particularity that depicts undisguisedly his ‘living Irish flesh and blood’.

Daniel O’Connell is mostly viewed as a restless, anxious, and intense man. Nevertheless, his correspondence discloses some unexpected features and characteristics. The letters to his wife, Mary, are little known and these form a significant and valuable presence in the volumes. Towards her O’Connell is everywhere as loving, calm and attentive as in this letter from 1827:

Since I wrote last I have been very well and very busy, bustling all day and sleeping soundly all night with my heart warm with the fondest love for my wife and children. (Letter 1436).

These are honest and deeply touching words. Even today, a woman would cherish such a plain, loving and reassuring message, even if it came less personally in an e-mail or in an electronic chat (though a scripted letter in one’s hand is somehow always more profound). What is remarkable is the unwavering consistency of O’Connell’s affection throughout the turbulence of his life. As D.L. Keller writes in his Great Days with O’Connell, the politician’s married life was one extended and unruffled period not only of ardent affectation but of courtship.

Some letters show the active part that O’Connell took in the day-to-day life of his wife and children (five sons and three daughters), even from afar. He gave advice and opinions, living as he did with his family ever in his thoughts and heart, especially when they were separated:

I had this morning a letter from our darling Maurice that does the greatest credit to his head and heart. He will ever be my dearest treasure, …Betsey and Nell and her husband are quite well. (1827, Letter 1434)

Domestic concerns apart, Daniel O’Connell also shared in detail with his wife his political plans and activities, and we should remember that this is at a period when women had few social rights and generally did not participate in public life. But with O’Connell there is no separation: his wife is a counsellor to him. She gives him support and understanding. Thus, in Letter 1432 (1827), addressing her as ‘darling’, he writes:

You will see in the papers an account of a great meeting with the Lord Mayor in the chair. It looks well, darling, and if followed up will lead to good results. (…) I really do expect Emancipation this sessions. I think indeed that it is almost impossible that they should be able to postpone it longer.

The correspondence continuously reveals the author’s hard and relentless political struggles, mainly with conservative Tory ministries, for Irish Catholic emancipation (which he achieved in April 1829) and Repeal of the Act of Union (which to his heartbreak he failed to attain). His opinions are straightforward and arresting and couched in simple persuasive logical arguments. We have just to look at Letter 2064 (1834) regarding O’Connell’s repeal motion in the House of Commons:

We close the debate this night (…) It indeed turns upon the single fact, whether or not Ireland has prospered by or since the Union. Rice figures Ireland into Prosperity. Is Ireland prosperous? Whoever thinks not refutes Rice’s entire case and that of the Unionists. Whoever says “Yes” gives Rice the victory. This in one line is the state of the argument. I need not say how triumphant, alas! does the real misery of Ireland render our case. In haste.

The argument is very precisely stated. But it is also presented in high-spirited and action-inspiring terms. O’Connell’s language bristles with life.

In the political correspondence we can see another personal characteristic: his compromising nature. He reflects on every side of a subject before reaching a decision. He then seeks common ground with those persons whose opinions are not diametrically opposed to his. This open, generous and wise inclination is revealed in the broad range of his correspondents, from political same-minded friends and bishops to the Whig ministers and even some Tories. O’Connell is networking with all of them through letters and actions to achieve his goals for Ireland. Letter 1397 (1827) highlights this:

I gave the Sheriff Elect of Dublin a letter of introduction to you. I would wish that he should find me useful to him through my friends (…) I would, of course, want the assistance of Mr. Lamb, but then the result would be most powerful Irish support for the Administration (…) with an honest Chancellor (…) with a neutral Lord-Lieutenant – and with Mr. Lamb, I would forfeit my Head if we did not un-Orange Ireland and make the Protestants content and good and the Catholics devotedly loyal.

O’Connell is accused by some of his contemporaries of not organizing an armed revolution. His actions, however, are tempered and justified by circumstance, by a little sentiment, and by reason. His personal experience of the horrors of violence for political ends convinced him of its perversity: he remained adamant that ‘no political change whatsoever is worth the shedding of a single drop of human blood’. Perhaps, the most striking evidence of his readiness to negotiate and to reach his political objectives in a strictly lawful and constitutional manner is the support given from the Irish representatives to the Whigs in Parliament in the first quarter of 1835. Some historians even call it the first modern party coalition for keeping a majority in the House. Daniel O’Connell writes clearly and openly to Lord John Russell in February 1835:

I think I may venture to promise that the Irish members of the popular party will avoid all topics on which they may differ with you and your friends, until the Tories are routed, and that you will find us perfectly ready to cooperate in any plan which your friends may deem most advisable to effect that purpose. In short, we will be steady allies without any mutiny in your camp. (Letter 2211)

The letter describes also how broad-minded the writer is in giving his unlimited and unconditional support to the allies. He goes even further. In his unselfishness he does not want personally to fill any public post or ministry. The ‘Liberator’ disavows achieving political power for himself: he is concerned solely in achieving as far as is politically possible ameliorated conditions for the Irish people. In this vein, in another letter from 1835, he writes:

You are aware that I did at once disclaim taking any office (…) I have been mostly highly flattered and thanked etc. for my conduct. I will also be more useful by influencing the appointment of others than by submitting to take any appointment myself. (Letter 2229)

Throughout the correspondence Daniel O’Connell’s individuality and personality are revealed to us as both rich and diverse. Sometimes, as he is human, they embrace contradiction. Certainly, he reaches out from his many letters to affect and touch the reader. His language and phraseology are everywhere concise and to the point. Taken together, the stretch of the letters preserved here in these volumes details one clear, dedicated and undeviating life. The Correspondence takes its reader on a rewarding adventure through turbulent times. The insights it provides both deepen and sharpen our knowledge of Ireland’s historical hero and better inform our perspective on our own current political times.