A Bookbinding Amateur

Left image

Right image

Text

A Bookbinding Amateur

I started repairing old books some seven years ago, around the time that my father passed away. Earlier, following in his footsteps, I had become an engineer and in this professional regard and in other ways I have always found reading books the most reliable route to learning. I have always been a book-reader and I tend to hold onto those I read; hence my collection is an accrual and assemblage of all sorts of books—new, second-hand, and old. I also inherited a set of old engineering books dating from the period 1940 to 1980 that my father owned. Of these, those that most required repair I restored rather amateurishly with a cocktail stick and some paper-glue; a simple but effective means to my end. Some of my father’s books were from the Pitman Engineering Collection and, more recently, I completed the full set: my first complete collection of any kind of literature, with books ranging in subject matter from thermodynamics to the mechanics of machines and from electrical technology to engineering economics.

In the process of completing my Pitman collection I visited many second-hand bookshops in Cork, Galway, Dublin, and London. My father-in-law once advised me never to leave a bookshop without purchasing a book; hence it became an interest and a hobby for me to collect old books (some on engineering, others not) and to repair and restore these where necessary. There is something about the feel of an old hardback that gets the heart going: the look, the feel, the smell, the quality of the book build. When we look at how today’s paperbacks are produced it is hard to get excited about them: mechanically cut, glued and pressed into mass production. Older books in hard-back covers were most likely hand-made by a dedicated bookbinder, carefully, one at a time. It is only when you look at a book from a book-binder’s perspective that one can appreciate the effort and expertise involved in building that singular book. The next time you have an old second-hand book in your hand, think about who the person is who originally made it. It wasn’t a machine: it was an individual like you or me.

On one of my trips to God’s own country in West Cork, I dropped into the Antiquity Bookshop café in Skibbereen. It houses a fine collection of new and second-hand books and offers one a place to sit down and enjoy a coffee whilst you browse: my kind of heaven. Why don’t more people do this? Anyhow, on my second or third visit there, I learned that the owner, Nicola Smyth, is married to a rare-book dealer, Holger Smyth, who has a vast collection of books at his home. By appointment, it is possible to visit his collection, and so in April 2023 I met with Holger, and he allowed me access to his treasure trove of books, vinyl, ephemera and art. What a day I spent there! Hour upon hour of delightful browsing and reading. I left with not one book but twelve! Not bad, considering I was faced with some 20,000 titles to consider. In the course of the day, Holger and I got talking about books in general and I said I had an interest in book restoration but was a rank amateur who had gone as far as one could without some sort of further specialist instruction. To my surprise he said he would ask his bookbinder in Germany if it would be possible for me to visit his workshop and to learn from him some of the techniques of the art of repairing and binding old books. Fast forward to February 1924 and I’m standing inside Bookbindery Diller in Frankfurt, Germany, with my apron on and my bone folder in my hand.

My host there, Ingmar Pons, is the proprietor of Bookbindery Diller. He is a professional bookbinder with master’s level qualifications in his craft. The company was founded originally in 1966 by Herr Diller. Today, it specialises in a combination of handcrafted bookbinding and state-of-the-art digital printing. They are real professionals here and the quality of their work is truly outstanding. No matter how old the book and its level of disrepair, they can restore it.

The first thing Ingmar asked me was what I wanted to get out of the week. My answer was twofold. I wanted to make a hardback book from scratch, and I wanted to repair some old books I had brought along with me. I knew I could only ever properly repair books if I knew how they were built and could fully appreciate the various steps you have to follow to make a book. We began and I soon learned that one of the most important elements of bookbinding is that of measurement and cutting. Everything you do has to revolve around the book-block and its dimensions. From here, you measure and cut endpapers, spines, covers, fabric, head bands: all of it. You also quickly understand that you need a lot of small, precise hand-tools to do your work: a sharp knife, scissors, paint brushes, a bone folder, rulers, tee squares and your most valuable friend, the scalpel. And everything must be held together with glue: PVA glue, to be precise.

I started building a book block on the first day by stitching sets of pages together. It was slow going and I was a quarter way through when I realised I had made a wrong stitch. I asked Jenny, one of the binders there, what to do to put it right: it had been an hour’s work of painstaking effort. “Start again!” came the reply and I thereby learned a valuable lesson. “We only do perfection here, no mistakes. If you have to start again, you start again.” So, I started again and managed to get only one half of the block stitched by day one, at which point my book necessarily became a smaller volume than I had originally planned. The following day I started on a book with a glued block and then, slowly but surely, learned about the steps necessary in making a book.

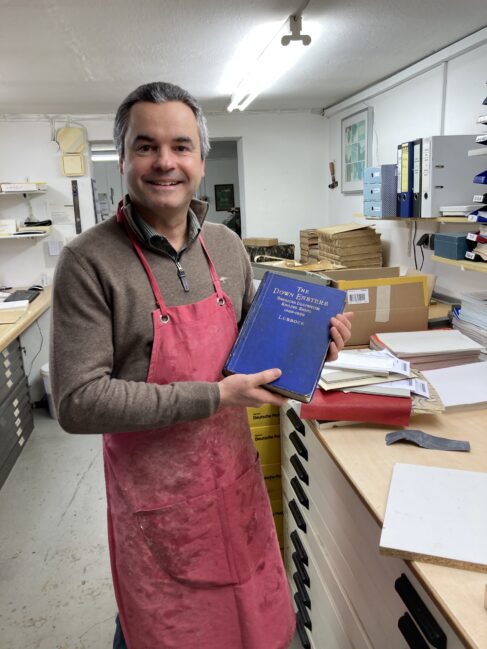

On the third day, I started to repair two old books I had brought along with me: the first an original 1929 volume of The Down Easters by Lubbock and the other a 1948 copy of Hansen’s Modern Timber Design. I assiduously disassembled the books, carefully removing the spines and covers and cleaned these as I went along. I reshaped the blocks, re-glued them, and remade spines and covers. Slowly but surely, the penny dropped on how these old books should be correctly reconstructed. As I finished on day four, I had two fully repaired books and had made two new journals, one stitched, one glued. Plus, I had now a deep appreciation of the craft and effort required to maintain old books. Ingmar, Jenny and Kira, who work at the Frankfurt binders, are masters of their craft and they make it look so deceptively easy. Each of them is university-trained in the techniques needed to restore all manner of books, from the seventeenth to the twenty-first century. The atmosphere in the bookbindery is one of earnest calm, and each day brings new challenges to be overcome. The workshop is roomy, with plenty of desk space, and the binders there spend most of their day working from a standing position. It also has an array of machines necessary to do their work: presses, stitching machines, embossing machines, and my favourite, the paper guillotine.

I left that Friday immensely grateful for the opportunity I had been given and full of revitalised energy to embark on my own book-binding career. I have since repaired twenty old books, all successfully, with varying degrees of finish. Hopefully, as the adage goes, practice will someday make perfect.