A World That Means Something - On the Quality of Art, Craft and Music

Left image

Right image

Text

A World that Means Something: On the Quality of Art, Craft and Music

Holger Smyth

In his book The Flamingo’s Style: Reflections in Natural History, Stephen Jay Gould writes that ‘Pristine originality is an illusion: all great ideas were thought and expressed before a conventional founder first proclaimed them.’

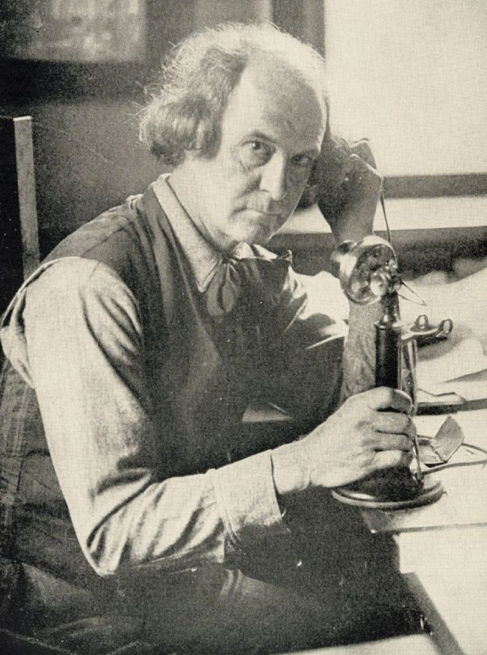

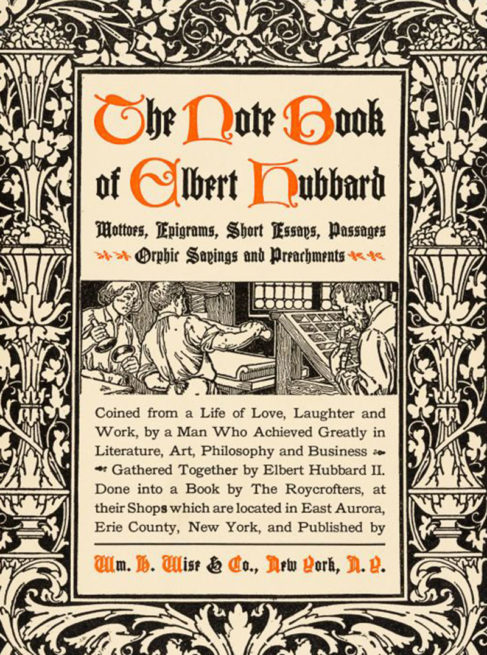

I am looking at the life of Elbert Hubbard, the ingenious writer, artist, philosopher, and founder of the arts and crafts community ‘The Roycrofters’ in East Aurora, New York, and I admire how openly he admitted the influence of William Morris with every pore of his life’s work.

But while many of us are silent in our admiration for Morris’s work, Hubbard was willing to copy the styles, philosophies, and longing of his English counterpart and start his own, similar movement in the States. How wonderful when someone is able to recognise the achievements of another and feel they want to continue in their path; and how comforting it is to realise that some of us do not settle for mediocrity but strive for quality.

In his account of William Morris in 1911, the great essayist Arthur Clutton-Brock wrote:

Morris said that our present society was in a state of economic war, and that for that reason it was anxious, joyless and impotent like the life of a savage tribe engaged in incessant vendettas. The economic peace which he desired was one in which men would have leisure and power to do all that was best worth doing; and he hoped to bring that peace about by filling them with his own desire to do what was best worth doing.

Clutton-Brock also realised about Morris:

It is easy to call him a visionary; but visionaries are necessary to every movement, because they alone can give it direction, and they alone can make men desire the goal towards which they move. It is not enough to preach peace by talking of the horrors of war; for men are so made they prefer horror to dullness. You must persuade them that peace means a fuller and more glorious life than war, if you would make them desire it passionately.

We must first understand Morris in order to understand Hubbard’s passion, the striving for a better life, a life with more quality for all, which was clearly instilled into Elbert Hubbard after a visit to Kelmscott in 1894. The very next year Hubbard founded the Roycroft community, which by 1910 had attracted 500 people. Hubbard’s ideas were also thriving thanks to an essay he had written in 1899, ‘A Message to Garcia’.

This inspirational essay was a landmark publication that reflected not only Hubbard’s despair of finding adequate employees but also his praise for those inspired and spirited fellow Roycrofters who made him realise who was with him on his journey and who was not helping him on the path to make the Roycroft community a success. I urge you to read it.

It tells the story of young Lieutenant Rowan, who takes on an impossible mission during the Spanish–American War and who throws everything and more at his task of delivering an important letter from US President McKinley to the leader of the revolutionary forces in Cuba, Calixto García. According to Wikipedia,

‘The essay bemoans the difficulty of finding employees who obey instructions without needless questions, work diligently without supervision, take initiative to overcome obstacles, and complete assignments promptly. It bewails the number of incompetent, lazy, thoughtless, obstructionist, employees who impede the work of the good employees, while admitting that these benighted people may not be able to help themselves.’

Wikipedia continues,

‘“A Message to Garcia” was originally published as a filler without a title in the March 1899 issue of the magazine The Philistine, which Elbert Hubbard edited. It was quickly reprinted as a promotional pamphlet for the New York Railroad, then as a book. It was very popular (especially amongst employers), and more than 40 million copies have been printed, in 37 languages. It also became a well-known allusion of American popular and business culture until the middle of the twentieth century. According to language expert Charles Earle Funk, “to take a message to Garcia” was for years a popular American slang expression for taking initiative and is still used by some members of the military.’

The essay and its message are still used today by inspirational speakers, and probably every day in pep talks on military bases around the world. And of course it is still in print in multiple languages and even used in Sunday sermons. Pastor Don Hooser in Dallas has written:

In his booklet, Hubbard goes on to lament the deplorable lack of men and women like Lieutenant Rowan – people who are willing to take on responsibilities and see them through to the end; people who don’t need someone to look over their shoulders to keep them on track; people with a strong work ethic; people who get the job done, done right, and right on time.

Visionaries like Hubbard and Morris depended on multiple Rowans. Today, sadly, a lack of inspired workers and also consumers defines a crisis in arts, crafts, and communities. It is difficult to inspire if no one wants to be inspired, and even more so if no one sees the value of ideas, craftsmanship, originality, and the upholding of quality standards.

Farmers’ markets with artisan producers of food, furniture, and crafts exist in communities that have road signs with slogans like ‘Shop Local’ in big letters, yet they are struggling because not enough locals support them or are willing to pay more for the healthier, more wholesome, and often fairer products one can obtain at these weekly happenings.

But for craftsmen, artists, and food artisans the biggest problem is not just the lack of buyers but the contradiction of communities that are willing to keep several supermarket chains afloat but will not bring their families to a local market and support quality just once a week.

Biographers of William Morris and Elbert Hubbard have stated that their movements were saddened, possibly depressed about the fact that they set out to create beautiful things and a better life for everyone, only to realise that the products from their workshops were expensive – they had to be, given the time and efforts invested.

This led to mainly wealthy people buying them, supporting the cause, and keeping the Roycrofters and Morris afloat. The poor, even the middle class, often could not afford the furniture, the architecture, the books. Of course this led to many people criticising the ‘socialist thought’ behind their movements as hypocritical. Hubbard especially had to fight this fight during his later years when it was suggested he was too commercial.

We live in a different time now. We can afford multiple trips to supermarkets every month, and the majority choose to go cheap every time instead of wholesome even once. What many forget is that there is a reason we still talk about Morris and Hubbard. The philosophies, the work ethic, and the products are so desirable that they are timeless. Today, Morris’s and Hubbard’s ideas and philosophies are available to everyone; in a fairly priced book or in an article on the internet.

Elbert Hubbard famously wrote: ‘I would rather be able to appreciate things I can not have than to have things I am not able to appreciate.’

No one will talk about the plastic toys produced in China for an army of indifferent consumers in the West, other than to lament the mountains of waste we have left our children – this instead of leaving them one toy they will remember because of its uniqueness. While the furniture of Morris and the Roycrofters is of immense value today, many of us have made countless trips to Swedish furniture shops for pleasure that does not last.

Equally, the world of antiquarian booksellers is facing more and more clients who look at books on our shelves and then go home and order them on Amazon. In doing so they condone the unfair treatment of Amazon’s workforce and the impossible treatment of sellers on Amazon. Contrast this with the fact that shops write receipts, pay taxes, have real employees with fair wages, and try to hold on to a system of retail that seems obsolete but is still needed to prevent ghost towns from emerging everywhere.

But there is a truth in knowledge after being in retail for more than thirty years and in the antiquarian book trade for more than twenty-five: It is not just the rich who buy quality. The majority of people desiring good-quality furniture, clothes, art, or rare books are the ones who barely have anything to spare and who would scrape together the last bit of money to buy a book or other meaningful item – often not for themselves but for their loved ones.

This fact, that making a meaningful gift can be an important message to people we love, is the true understanding of quality. In that moment, we understand value. We appreciate the time, the labour, the thought process behind an idea, and that this all amounts to the price of something. Quality is for everyone, and it is available. But every new generation is losing it again and again when it is not willing to pay for it.

Elbert Hubbard also wrote: ‘Folks who never do any more than they get paid for, never get paid for more than they do.’ He understood how the success of spreading the wish for quality relied on his being an exemplary employer but also on his workforce to be dedicated. The same dedication is needed from all of us in our communities in the moment we turn into buyers.

Last night Salvador Sobral’s poignant song ‘Amar Pelos Dois’ won the Eurovision Song Contest for Portugal for the very first time – a song whose lyrics few understood, because they were sung in Sobral’s mother tongue, Portuguese. The timeless and beautiful tune and the audacious young man’s presentation were enough to persuade the hearts of millions to vote for the song.

When he had a chance to speak, twenty-seven-year-old Sobral said, ‘I want to say that we live in a world of disposable music – fast-food music without any content. And I think this could be a victory for music with people that make music that actually means something.’

We all know he is right, and we all know his demands can be applied to many things in our society. Not only William Morris and Elbert Hubbard but also Salvador Sobral and his sister Luisa, who wrote the song, want to live in a world that means something.

There is no socialism here, no Marxism or capitalism, only communities that will fail or thrive with our children turning into young adults with question marks on their forehead:

Where do I go and what should I do?