We All Are Refugees,

At Least Once in Our lives.

‘What we need are hearts on fire’*

Left image

Right image

Text

We All Are Refugees, At Least Once in Our lives

‘What we need are hearts on fire’*

Holger Smyth

Antiquarian booksellers of the world, dealers in the printed gems that carry political ideas, philosophies, and empathy through poetry and literature, live by a code of ethics that was given to the world by the Antiquarian Bookseller Association of America in New York in May 1927. One of the many articles in that code is the wishful thinking that ‘the head of the business should be a man of high character and of sound integrity’.

Now that sounds just like the job description for a president we all would like to see at the top of our nation, or for a man we would like to call father, husband, brother, or friend. Because this code was written only a few years after women gained the right to vote, it neglects to mention that a woman could also be head of a book business. Sadly today, ninety years later, most book businesses still carry the name of a solitary male, even though their often female wives and partners are as present in the trade and as important for their success as the ‘man of high character’. Only recently, a German female colleague at an international fair was asked by a collector if her boss was around.

Many bookseller and other organisations in the world have similar codes, written or unwritten, and while many wished the code would be law, these codes were written by humans who wanted to impress but in the end so very human are the subjects of all organisations.

We wish to be better and fairer than we are, and at the end of the day we all hope that, maybe not by the measure of sometimes spoiled relationships with our parents but definitely in the eyes of our grandparents, we would be considered decent and kind. That is the real test, and that is where many of us have to bow their heads.

Libraries and bookshops all over the world are safekeepers of our heritage of progress. Progress in humanity and fair play. On the shelves of these libraries and bookshops we find speeches of founding fathers of many nations, politicians who try to persuade with their memoirs, and writers who use fiction to transport ideas of change and rattle us all to the present needs of a humane world.

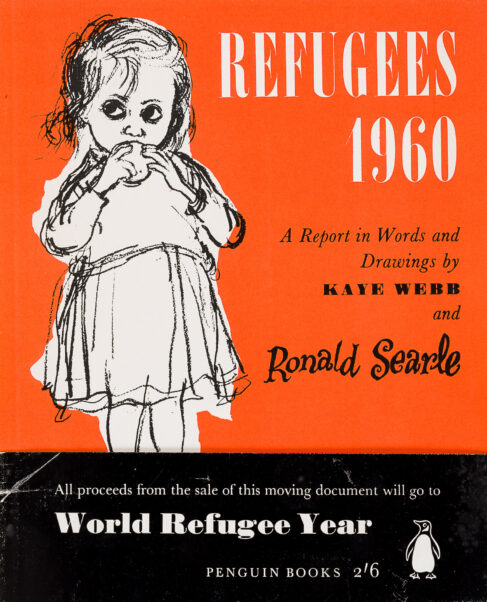

But today in 2017 it is not one of the landmark publications of a famous philosopher, historian, or sociologist that puts us all to shame and questions the approval of our grandparents, great-grandparents, and all before them. It is a slim Penguin book, published in Great Britain during the ‘World Refugee Year’ 1959–60. In explanation of this event, the Anne Frank Guide notes:

Many refugees remained in camps almost fifteen years after the end of the Second World War. This was seen as disgraceful by those who had suffered greatly during the war and those who were concerned about their situation. It was at this point that the United Nations launched a program to resolve the refugee problem once and for all. 1959–1960 was announced as World Refugee Year. The aim of this project was to ‘clear the camps’. It achieved some significant results, especially in Europe. By the end of 1960, for the first time since before the war, all the refugee camps in Europe were closed.

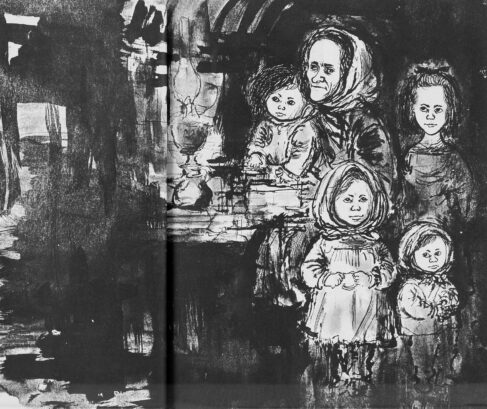

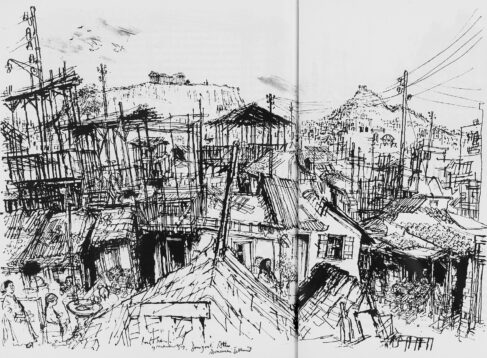

The Penguin book in question was a ‘report in words and drawings’ by Kaye Webb and Ronald Searle, and with its subtle drawings it reflected powerfully on the situation of refugees without robbing them of their dignity through all-revealing-photographs. Graphic photographs we often see today, showing the despair in all clarity but obviously with less impact on our empathy than ever.

The words in that little publication are powerful and have not lost their validity. It is heartbreaking to read the efforts of the writer Kaye Webb, since her appeals echo in the reports, pleas, and hopes of refugees today, nearly sixty years later. Page 38 of the 1960 Penguin booklet reads:

Since Greece is almost entirely surrounded by satellite countries, and so is in a precarious and delicate geographical situation, it is inevitable that her ‘foreign’ refugees should be regarded with suspicion, and all new arrivals are subjected to the most rigorous examination… Most of them are young men now willing to accept emigration under any conditions to Canada or Australia or South Africa, but they dreamed, originally, of going to the United States… Most refugees arrive at Lavrion, and its companion camp on the island of Syros, in clothes which are threadbare from weeks or months of hard manual labour in the military border camps… Greece’s other refugees include seven thousand Armenians, two thousand of whom have made shanty homes for themselves in the district of Athens called Dourgouti. Their flimsy shacks of old wood, flattened petrol cans, plaster, scavenged bricks, even old rugs and matting, often split at the seams when the rains come, but soaring above them is the lovely indestructability of the Parthenon, and each year some among them gaily forecast a miracle when ‘all this will be swept away and we shall have good dry houses’. To rehouse this particular group would cost an estimated two million pounds [roughly 32 million pounds sterling in 2017].

Does that all not sound too familiar?

If we judge the world’s ability to react fifteen years after the end of World War II with empathy and action, if we see the catastrophe of displacement for victims and aggressors in 1960s Europe and compare it to the epic drama of post-famine Ireland in 1850, we see an improvement.

Where is this empathy today when private initiatives are outperforming international aid organisations? The Penguin booklet asks the same question and answers it on page 48:

What is needed to empty the camps this World Refugee Year?

The answer is simple. Every country with room to spare should ease open its bureaucratic door and undertake to accept without ‘ifs’ or ‘buts’ a percentage of sick or economically useless human beings, to balance what they have gained from the young, healthy immigrants who will be benefiting their economy without any cost to them in education or training. A gesture of this nature on governmental level would gain active support. Individuals who care could then provide the cash, care and patience needed to get these abandoned human beings happily established in a country they could call their own.

Some refugees may be ungrateful, unlovely, difficult.

Some may turn out to have become permanent beggars.

But if they are any of these things we have helped to make them so – by years of neglect and indifferent charity instead of positive help.

It is a risk a nation can afford to take. For the children will flourish and put down roots and the dank, dismal, hopeless camps of Europe will no longer be on the conscience of what we like to call the Free World.

The shame I feel when I read these lines is immense.

As bookdealers we see many publications crossing our desks, with many wonderful ideas, formulated in past centuries. The amount of forgiveness we all need for our neglect is nowhere to be found if we consider our reactions to people in need since the war in Syria has made us all indifferent.

A famous quote by Elie Wiesel is: ‘The opposite of love is not hate, it is indifference.’ What a remarkable and powerful thing to say – and, like many important quotes, repeated and rephrased many times but unheard and forgotten. Since our attention span for quotes like this is not enough, here is another by Wiesel: ‘There may be times when we are powerless to prevent injustice, but there must never be a time when we fail to protest.’

The breakthrough for all of us would be to ask: How can I help? While the answer would be different for everyone, we do have an answer to this question. Another breakthrough would be to allow ourselves to accuse and ask questions and demand answers even though we ourselves are not perfect and can be called out on our double standards. We need to ask and grant forgiveness, with or without God, with or without religion.

But first we need to gain the respect of our grandparents again, be they dead or alive. Our code of ethics has to change, as the codes of the bookseller associations worldwide are only a pretentious guideline for super-humans in which no one is allowed to transform from Saul to Paul while everyone lives in a Christian society.

Elie Wiesel, whom the Nobel Prize Committee called ‘a messenger to mankind’, was one of the most respected survivors of the Holocaust. He found his calling, writing fifty-seven books during his lifetime, never stopping to try to persuade, remind and remark.

His work did not stop at remembering Auschwitz or Buchenwald. He was one of the founding members of the Human Rights Foundation in New York, an organisation that was founded to seek human rights for every race and colour. His controversial opinions on the expansion of Israeli settlement make him one of the best examples of the fact that no one can hope to be perfect yet they can still try to be a good person, an ambassador for peace.

We all are refugees at least once in our lives, and we all know of hospitality as a worldwide tradition of many nations in western or eastern civilisation. What we now need are hearts on fire to look to our bookshelves and see the promises we have given ourselves through the ages of printing.

‘We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.’ —Elie Wiesel.

* From Kurt Elling’s lyrics to ‘We Three Kings’.