Autobiography of a Printmaker

Left image

Right image

Text

Autobiography of a Printmaker

Brian Lalor

My awareness of prints and printmaking occurred in a very direct manner: I asked a question and was intrigued by the answer. In my final years as a schoolboy, I had been a dedicated collector of items of material culture: coins and medals, fossils, militaria, ethnography, and had recently acquired a beautifully illustrated mid-nineteenth-century book on English coins.1 I asked my mother (herself the daughter of an artist) how the illustrations were done. ‘Oh,’ she said, ‘lithographs, they are created on a special kind of stone and printed from that.’

Following this explanation, I began to look at the print illustrations in books and to try to understand their particular visual language. My next print purchase (by then I was an architectural student at the Crawford School of Art in Cork) was not just another volume illustrated with prints but an introduction to one of the greatest artists to work in the medium of engraving – and also one of the most profound social commentators of the eighteenth century, William Hogarth.2 These illustrations were not the artist’s original copperplate engravings but nineteenth-century wood engravings of Hogarth’s subjects executed by a lesser hand. Lesser maybe, but to my novice eye a nonetheless enticing excursion into the possibilities of the world of print. These two unrelated purchases stimulated an interest, a preoccupation and a professional artistic path that has moulded my career as artist, writer and collector ever since.

Some years later I moved to London to continue my studies. It was there that my involvement with prints first developed and I began to appreciate the vastness and complexity of the subject. The print collections of the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum became favourite places to visit. I also discovered the quiet and discreet premises of the print dealers. Here one could browse and become more intimately familiar with the work of printmakers of the past. These visits were profoundly significant occasions for me, as I was closely examining work by many of the world’s finest printmakers and discovered the extreme delicacy and beauty of their art.

All of these historic prints captivated my imagination yet also sent me to look at contemporary printmaking in the Bond Street galleries of the city where the best of the modern masters were on show. My focus was towards the printmaking of the past, and however exciting the prints of Picasso or Matisse might be, I continued to return to the premises of the dealers and the institutional print collections. I had not at this stage made any prints of my own but was sufficiently enamoured of the discipline that it was only a matter of time before I began. My studies then occupied all of my time, so venturing into actual printmaking did not occur until some time after I had left London for good.

A predilection for artist-craftsmanship rather than the free expression of late twentieth-century modernism can be explained by my family background. Rather than attending school, I had spent my early childhood (during which I was ill with polio) in the house of M.J. McNamara, my maternal grandfather, an artist trained at the Royal College of Art and Paris studios and a pioneer of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Ireland. He had been a member of the Guild of Irish Art Workers, an association that included some of the leading Irish artists of his day, Jack B. Yeats, Sarah Purser and Oliver Sheppard. The McNamara household was a shrine to Arts and Crafts ideas, Japonaiserie and fin-de-siècle aesthetics. These were influences that I absorbed unawares, and they were to shape my approach to areas of the arts that subsequently engaged me, those dependent on a high degree of craftsmanship in the interests of artistic expression.

Following my studies in London, I moved to Munich where I worked with an architectural firm designing houses and schools. My drawing abilities were held in high regard and I was given significant projects to work on. When free to roam the city I studied the work of the German expressionist printmakers of the Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke in the collections of the Lenbachhaus and Sammlung Schack galleries. These exposed me to artists I had not encountered amongst the London print collections and made me aware of the power of the relief print.

A further move, to Tel Aviv in Israel, brought me closer to beginning engagement as a printmaker. My initial job with a prominent firm of architects enabled me to work in international architectural competitions and in theatre design. I had the pleasure of being a prizewinner in the Max Reinhardt Theatre Competition of 1969. However, I had been on the lookout for an opportunity to do some work in the ever-expanding field of archaeology, and stepped into one of the most significant posts then available as the head of the architectural department of the Hebrew University / Israel Exploration Society’s Temple Mount Excavations in Jerusalem.3 This project, exploring the remains of the first-century Temple of Herod the Great, the acropolis of the classical city and one of the greatest architectural achievements of the ancient world, was to occupy me for the next five years and to provide me with the challenge to attempt to solve a century-long enigma in the history of the city.

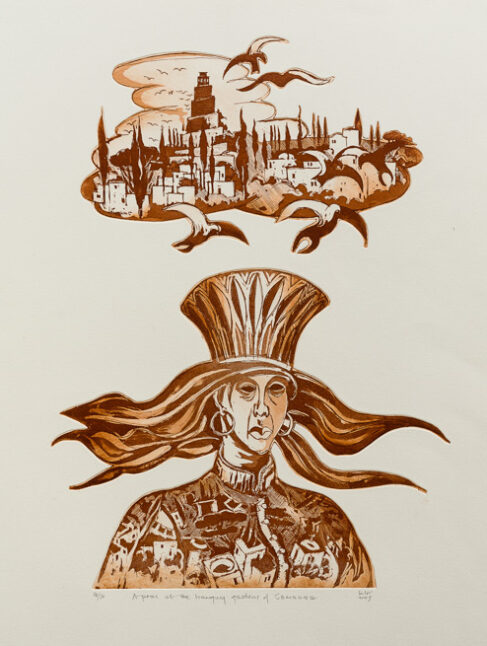

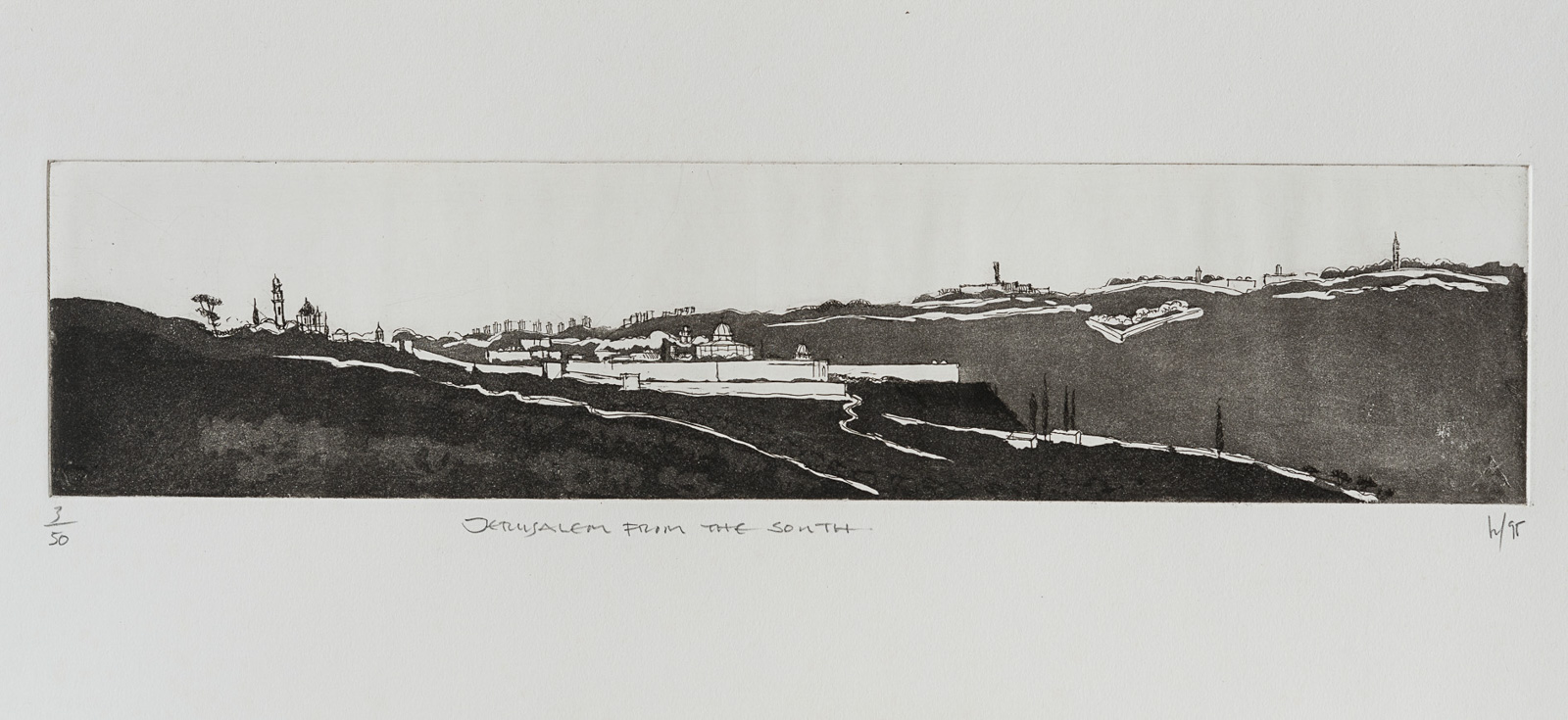

It was in Jerusalem that I made my first prints, very small etchings devoted to architectural and figure studies. I worked briefly in the print department at the Bezalel School of Art and very soon was able to master the rudiments of producing a respectable etching. The street markets of the medieval walled Old City, the vaulted souks built by the Crusaders, were fascinating to walk through, and one day in a stall dealing in metalwork I found a small etching press. In a short time I had a print studio set up in my home in the Palestinian village of Silwan, just outside the walls of the Old City and within sight of my excavation. Purchasing the acids and other equipment required the ability to compromise and make do with what was available in the street markets. Ultimately, almost anything I required, the traders of the Old City were able to supply. Another metal merchant flattened sections of an old copper water cistern to provide me with plates to etch upon. A toolmaker made etching tools for me while a spice merchant provided resin, a paint dealer asphalt varnish. Going to their stalls was like visiting the lairs of ancient alchemists. No conversation or request for assistance could be discussed without the ritual politeness of sitting together sipping tiny cups of black coffee while sharing the news of the day. After formalities, I could broach the subject of my latest technical problem. I might as well have been a workshop apprentice in fifteenth-century Amsterdam; everything had to be handmade, and slowly. Over the succeeding years of my residence in Jerusalem, I produced a corpus of etchings in small limited editions, my subject and treatment expanding, the scale of what I attempted becoming more confident.

My major archaeological achievement of these years was producing a solution to the monumental entrance of the Basilica of Herod the Great, a problem that had engaged scholars since the nineteenth century. My proposal was based on the fragmentary excavated evidence, backed up by principles derived from classical studies. This proposal was initially regarded with acute scepticism by the excavation team and proved highly controversial. Time passed; conclusive evidence was excavated. Eventually, my reconstruction received widespread acceptance. Almost fifty years later, my theory remains the definitive interpretation, reproduced in many reports and scholarly journals. The Jerusalem Guide, illustrated with over a hundred of my line drawings, was published in 1973, accompanied by a portfolio of the illustrations.

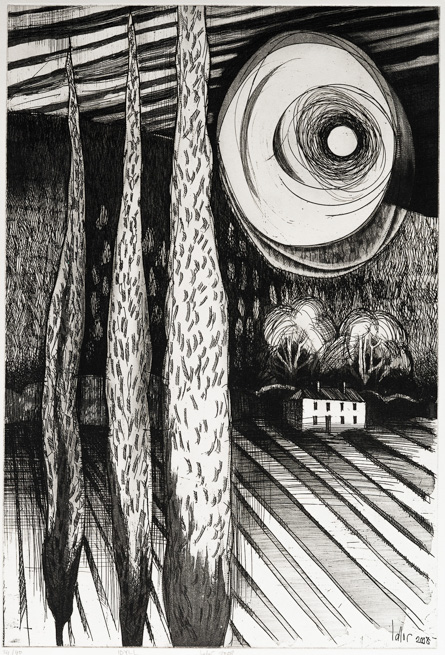

In 1974 I left Jerusalem to return to Ireland, got married and settled in West Cork where I opened a print studio and devoted myself to a full-time life as artist and writer. With a growing family I abandoned archaeology for a period. Over the next ten years I produced a wide range of etchings and woodcuts, largely devoted to the architecture and landscape of the region. From the 1970s I exhibited widely, with solo exhibitions in Ireland, Germany, Switzerland and the United States. Invitations during the early 1980s led to the production of two substantial portfolio collections of prints, Kilkenny, City and Topography in 1982 and The Myth of Icarus in 1985. In Zurich I had been exhibiting a set of large etchings, a number of which were concerned with early aviation: flight, balloons and the Icarus/Daedalus legend. An executive of the Swiss flight reinsurance firm Swiss Re visited the exhibition and commissioned the Icarus portfolio, devoted entirely to flight. My first published collection of prints with a narrative text followed in 1990.4

By the late 1980s I had returned to archaeology, joining the Washington DC Smithsonian Institution’s excavations at Tell Jemmeh,5 a Bronze Age city site close to the Gaza Strip and originally excavated by Sir Flinders Petrie in the 1920s. Petrie was the father of stratigraphical analysis in archaeology and a pioneer of applying scientific methodology to exploring the past. As in my work in Jerusalem, with the Smithsonian excavation I made important discoveries, on this occasion regarding mud-brick construction methods in architecture. The Tell Jemmeh seasons were held annually in July–August and the team worked under gruelling conditions, from 4 a.m. until midday. For a period I was acting director of this excavation due to the illness of the director.

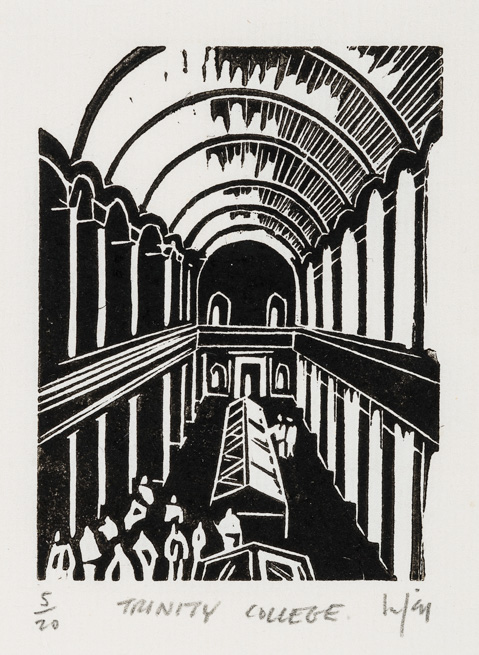

In 1998 I left West Cork for Dublin and it remained my base for the following twenty years. In a vaulted studio on the sixth floor of a former nineteenth-century sugar mill overlooking the Grand Canal, I began to concentrate on relief prints, initially small scale for book illustrations but graduating to woodcuts and linocuts of much larger dimensions. Four books of prints from this period, Dublin Drawn and Quartered (1991), Ultimate Dublin Guide: An A-Z of Everything (1991), The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1997) and The Laugh of Lost Men (1997) contain some of my best work in the medium of woodcut where the balance of areas of black and white can be exploited to achieve dramatic or emotional effects. Oscar Wilde’s text for The Ballad provided me with an opportunity to explore the only Wilde text in which the poet abandons his façade of witty epigrams in order to confront human suffering. This publication had a number of readings, none more memorable than one in Dublin’s eighteenth-century Kilmainham Gaol with an astonishingly vivid two-hand reading by the Joycean actor Barry McGovern and the socialist intellectual Liz McManus.

From Dublin I continued to participate in archaeological expeditions, with the Smithsonian Institute, France’s Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the British School of Archaeology, Bar Ilan University, and many other academic bodies. The most significant of these expeditions was to Khirokitia in Cyprus, a Neolithic city site c.7000 BC, one of the earliest urban settlements to be identified.6 The artefacts from this excavation left me with a deep respect for the aesthetic sophistication and sensibilities of early human society. From Cyprus to Turkey is a logical extension, and in Istanbul I produced numerous line etchings of Ottoman architecture.

In 2005 I became board chairman of Graphic Studio Dublin (Ireland’s oldest cooperative print atelier, which I had joined in 1991) and was instrumental in the acquisition of Distillery House, a permanent home for the studio and the establishment of its state-of-the-art premises in a spacious four-storey nineteenth-century warehouse. Here, artists from all over Ireland and abroad come to study printmaking and, in the vision of S.W. Hayter who established Atelier 17 in Paris in 1927, to bring together artists of the highest rank with emerging talents, to work together and in a harmony of endeavour.

A culmination of my work in print came in 2010 with a thirty-year retrospective, Voussoir,7 at Graphic Studio Gallery in Dublin and, in the following year, the publication of Ink-Stained Hands,8 a pioneering and definitive history of the emergence of studio printmaking in Ireland during the early twentieth century. The Voussoir exhibition brought together representative examples of work in all the print media in which I practised, yet in some respects only touched the surface of a much larger subject, my involvement as print historian, lecturer and print collector.

Ink-Stained Hands (the title is a line from a lengthy poem in memory of the printmaker Mary Farl Powers by the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Paul Muldoon) records the coming together in the late 1950s of Anne Yeats (daughter of the poet), Liam Miller, founder of the Dolmen Press (Ireland’s first significant hand press), Elizabeth Rivers (celebrated English wood engraver) and two young artists, Patrick Hickey and Leslie MacWeeney, a group who revolutionised the graphic arts in Ireland. In late 2016, highlighting my activities as a print collector, the National Gallery of Ireland hosted an exhibition, Eclectic Images: The Brian Lalor Print Collection,9 a selection from the 150 European prints I gifted to the National Gallery in 2014. These prints, assembled throughout my career as a printmaker, concentrated on black and white images produced in Europe since the sixteenth century, with an emphasis on the development of printmaking as a primary vehicle in the communication of ideas.10

In 2009 I closed my Dublin print studio and returned to live outside the village of Ballydehob in West Cork where I had originally established my printmaking base in Ireland. Here I built a new studio and continue to contribute prints to exhibitions, most recently in Spain, Britain and the United States. An expansion of my work in a new direction has been to collaborate with ceramic sculptor Jim Turner in two exhibitions, the second of which, The Fertile Crescent, was devoted to the ongoing crisis in the Middle East with the destruction of communities and the loss of millennia of built heritage. My archaeological background facilitated automatic access to the historical aspects of a theme that resulted in a rich assemblage of painted porcelain vessels and small sculptures in obelisk and ziggurat form as well as some major, large-scale pieces.

In 2009 I closed my Dublin print studio and returned to live outside the village of Ballydehob in West Cork where I had originally established my printmaking base in Ireland. Here I built a new studio and continue to contribute prints to exhibitions, most recently in Spain, Britain and the United States. An expansion of my work in a new direction has been to collaborate with ceramic sculptor Jim Turner in two exhibitions, the second of which, The Fertile Crescent, was devoted to the ongoing crisis in the Middle East with the destruction of communities and the loss of millennia of built heritage. My archaeological background facilitated automatic access to the historical aspects of a theme that resulted in a rich assemblage of painted porcelain vessels and small sculptures in obelisk and ziggurat form as well as some major, large-scale pieces.

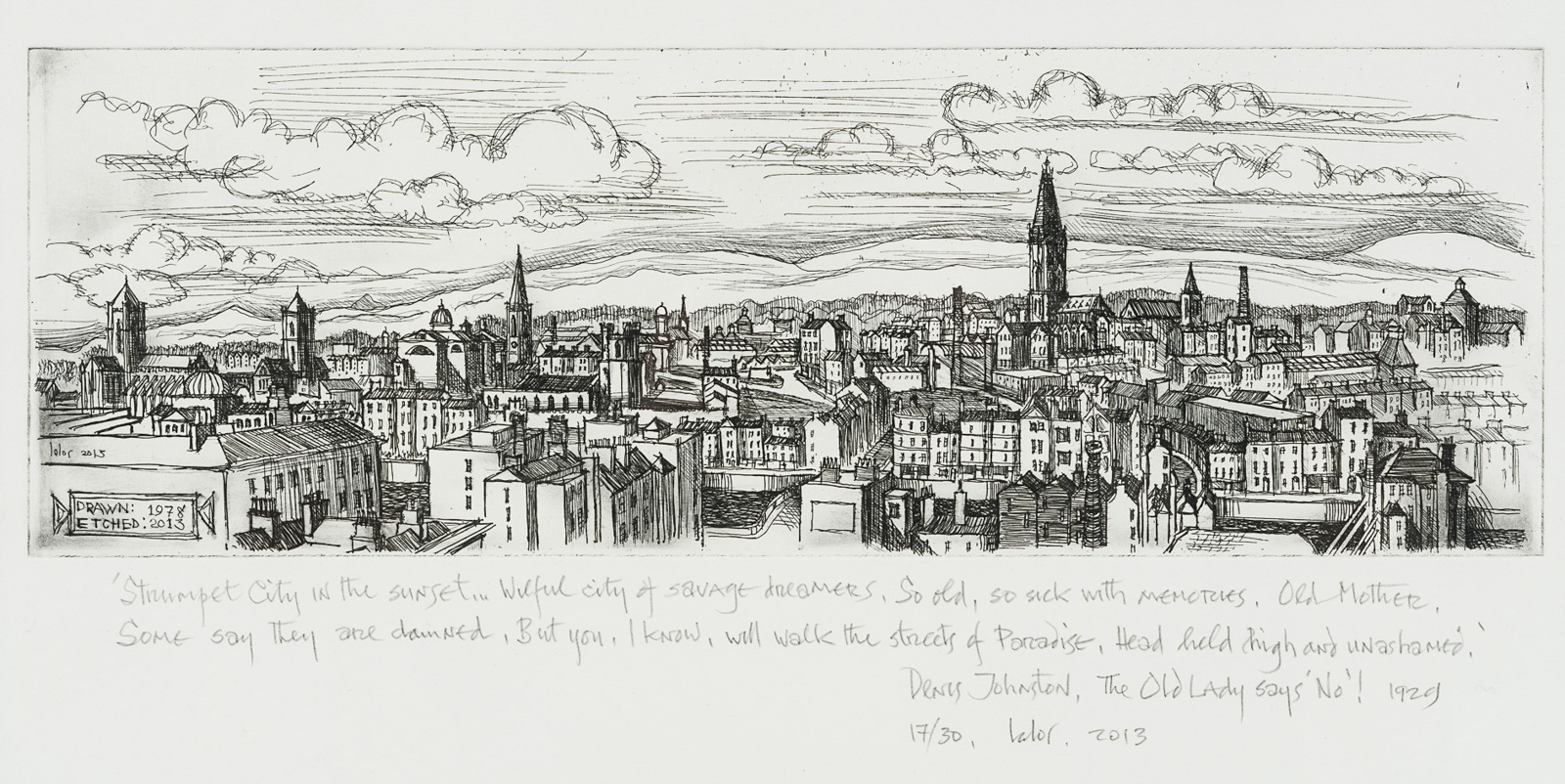

Urban topography has been an enduring theme of my work in all media, not just print, with extensive series of drawings, watercolours and etchings devoted to cities: Jerusalem, Rome, Dublin, Cork, Istanbul. The influence of my print collecting is visible in a predilection for the linear treatment of urban subjects after the manner of European woodcuts and engravings of cityscapes from the seventeenth century. In these works, art, scholarship, and archaeology combine to influence the choice of image and its final character.

Notes

1 The Coins of England, H.N.H. London, chromolithographs by F. Baur, 1846.

2 The Works of Hogarth, London, no author, no date, wood engravings, c.1890s.

3 The Complete Guide to the Temple Mount Excavations, Eilat Mazar, Shoham Academic Research and Publications, Jerusalem, 2002.

4 West of West: An Artist’s Encounter with West Cork, Brian Lalor, Brandon, Dingle, 1990.

5 The Smithsonian Institution Excavations at Tell Jemmeh, Israel, 1970–1990, David Ben-Shlomo, Gus W. Van Beek, Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2014.

6 Khirokitia: A Neolithic Site, Alain le Brun, Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation, 1997.

7 Voussoir: Brian Lalor Retrospective, Prints 1980-2010, Graphic Studio Gallery, Dublin, 2010.

8 Ink-Stained Hands, Graphic Studio Dublin and the Origins of Fine-Art Printmaking in Ireland, Brian Lalor, The Lilliput Press, Dublin, 2011.

9 Eclectic Images: Recent Acquisitions 2011–2016, The Brian Lalor Print Collection, The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, 2016.

10 ‘The Lalor Print Collection gets a rare run-out at the National Gallery’, Sean Dunne, Irish Times, 30 August 2016.